BOOK REVIEW:

On Alessandra Sanguinetti’s “The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer”

By Rafael Soldi | Published November 24, 2020 in Strange Fire Collective

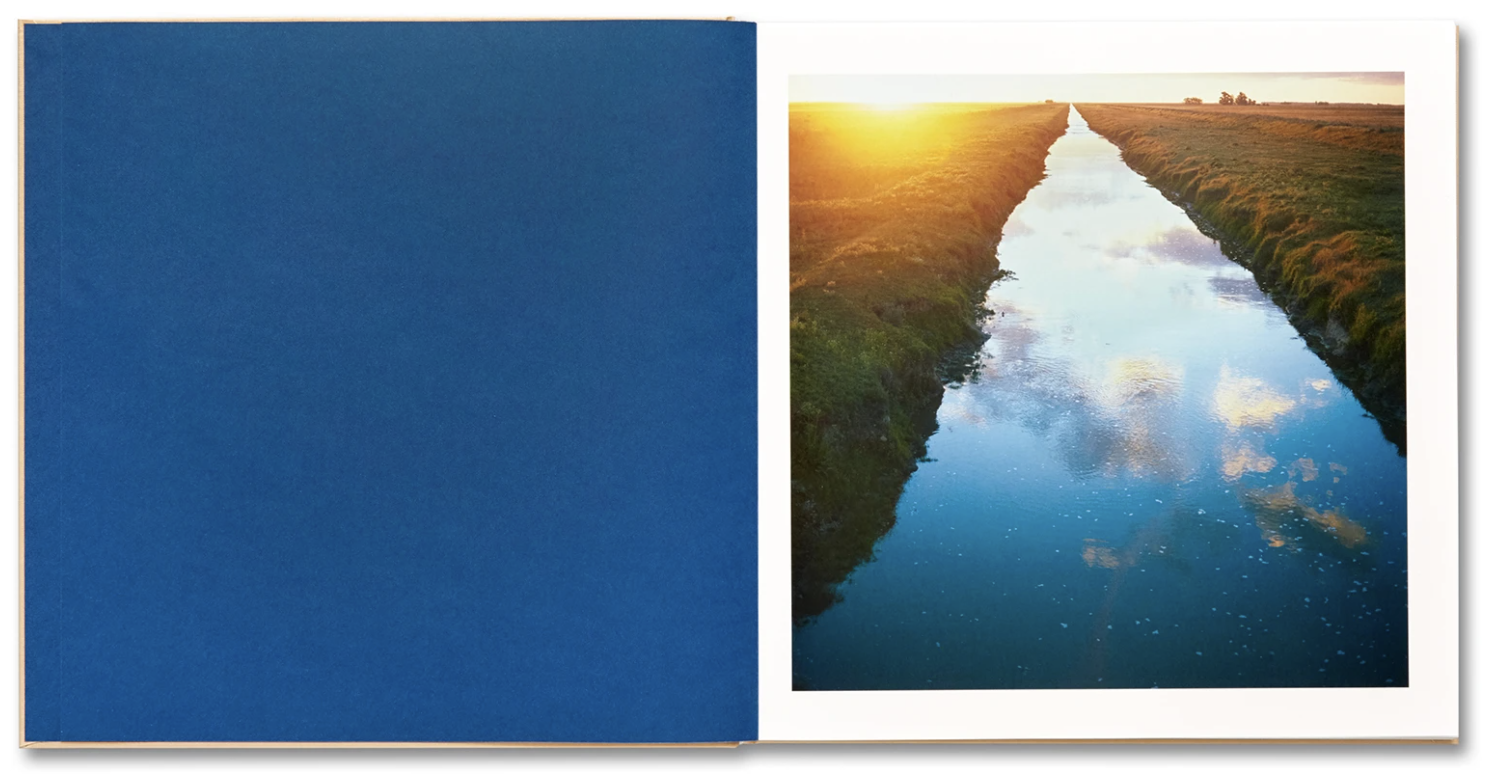

Left: Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Couple. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1999. Right: Alessandra Sanguinetti, from The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer

Left: Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Couple. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 1999. Right: Alessandra Sanguinetti, from The Illusion of an Everlasting SummerThis is evident immediately as we open the book and are first met by an idyllic landscape—an infinite river mirroring an impossibly blue sky as a glowing sun buds the horizon in the distance. We know right away that we are in a place unlike any other. On the next page one encounters young Guille and Belinda crouching at the water’s edge, their reflections crystallized on the surface against the deep blue sky. Notably, the image is upside-down so that their reflection is right-side-up. Sanguinetti’s decision to prioritize their reflected selves—as opposed to their flesh and blood—legitimizes imagination in a world—the farm—entrenched in the realities of sentient life and death. It makes one ask, is this dream-space a reflection of themselves, or are they a reflection of their fanciful subconscious?

In the first book we follow Guille and Belinda while Sanguinetti works to “crystallize their rich yet fragile and unattended world”. Each image is a rich tableau where they enact a fantasy reel of weddings, pregnancies, motherhood, and other scenarios. A decade later, we bear witness to the theatre colliding with the realities of rural daily life. Sanguinetti captures these moments with the same clarity and dignity that she brought to the earlier, more lighthearted days. Two photographs in particular jump out to me. There is a photograph in the first book titled The Couple, which portrays the two young girls embracing, holding one hand in front, with the other arm wrapped around each other. Guille’s back is to the camera, she is facing away in her underwear and bra. Belinda stares directly into the lens—grounded and erect, shirtless, with dark pants and a dark mustache, clearly playing the role of the man in this fictitious couple. Her lanky body is softly embraced by Guille’s larger one. In the second book we find an image almost identical in composition. This time “the man” is Belinda’s partner, a lanky man with dark hair, shirtless, wearing dark pants—eerily similar to the man she once portrayed as a child. They also hold one hand while the other is wrapped around him. Belinda’s gaze remains aimed at the lens, while her partner looks away as Guille once did. Moments like this bring these two books into beautiful synchrony.