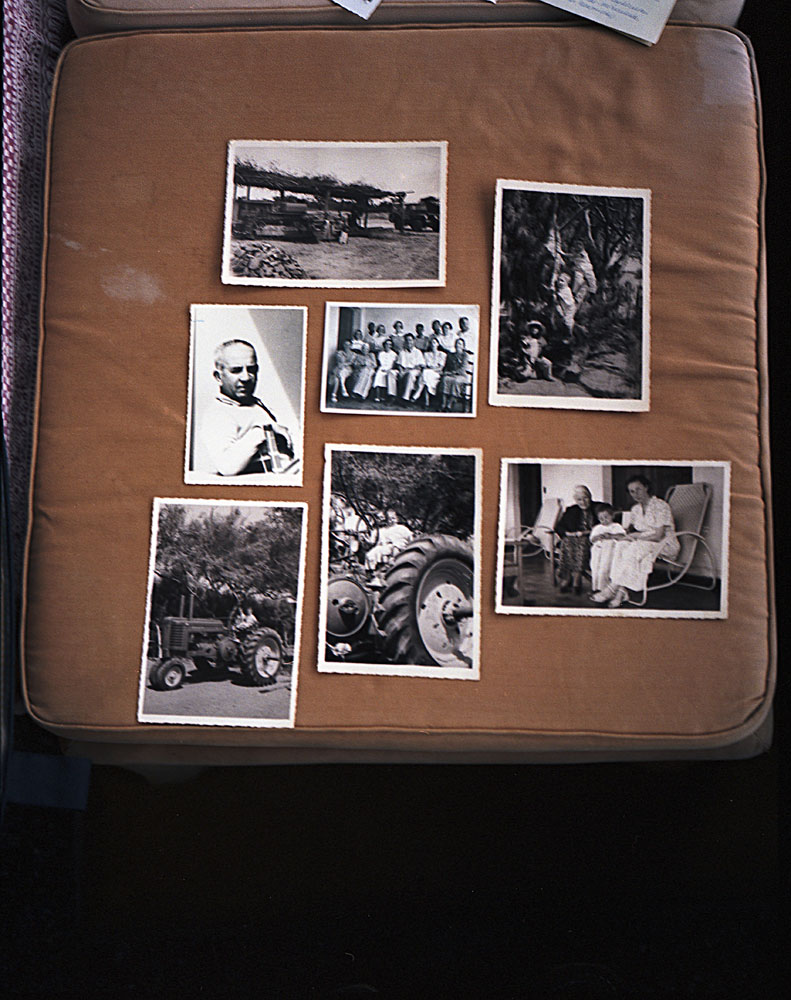

My Nonna, Anna Maria Soldi Gasca, was born in 1919 in Ovada, Italy. She was one of only seven women to graduate with a degree in Chemistry from the University of Genova in 1941, shortly before WWII broke out. My grandfather was born in Perú to an Italian immigrant and met my grandmother while on a trip to Genova. After the war ended my Nonna relocated to Peru, where they married and had five children. My grandfather—who managed a vineyard and wine cellar in the countryside of Peru, far from the city—died when the children were young, leaving my Nonna to raise them and build a life of her own in a foreign place.

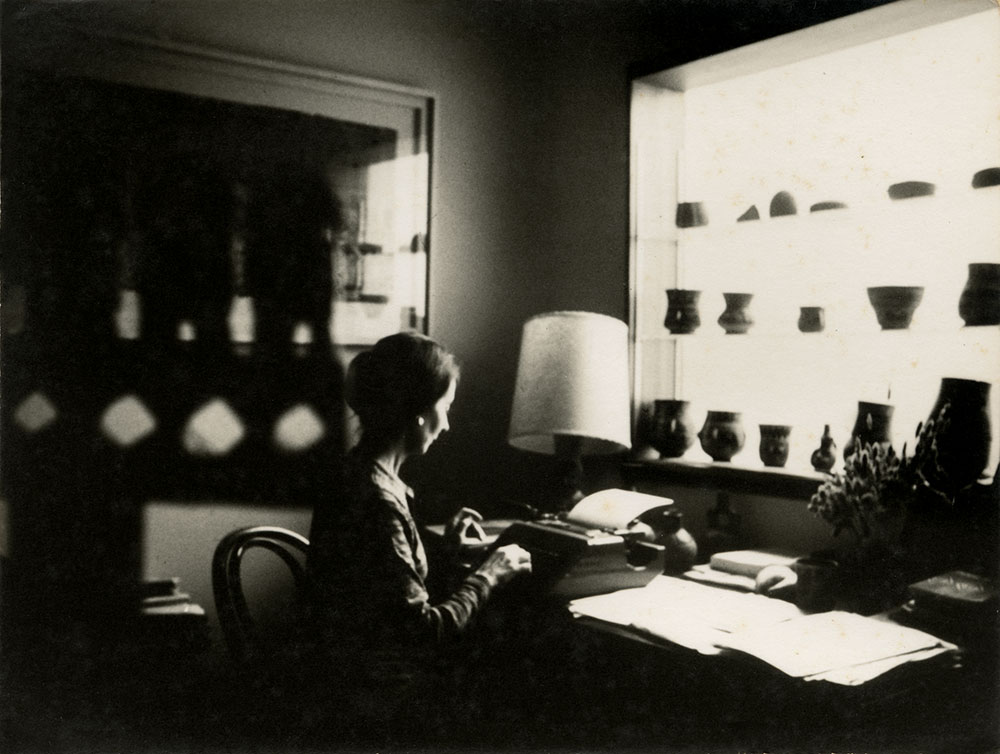

One of the most intelligent women I have ever known, my Nonna built a life as an archeologist and scholar—a published expert in Peru’s pre-Columbian history. She nurtured special lifelong friendships with people that went on to define their field together. I recently learned of her close friendship with a gay man, Craig Morris, a celebrated but unassuming scholar who managed to transform Andean archaeology. During his tenure at the American Museum of Natural History—from the 70s on—he visited Peru frequently with his partner. My Nonna became the couple's friend and right-hand in Peru, caring for a small apartment they kept in Lima. My father recalls a salon of sorts, with interesting people from around the world at the dinner table—the same table I shared with her 40 years later—some gay, some straight, all smart and fascinating. I often wonder if this life would have unfolded for her had my grandfather not died so young.

In the years before her death I was finishing my photography degree and becoming more serious about my work. She insisted I bring my portfolio with me on my next trip home so she could see it. I remember opening a portfolio of large prints on her bed and she drew the blinds so the sun wouldn't damage the prints—not unlike an ancient textile or artifact. We continued to have a conversation about every image. Her patience never exhausted, she was curious, thoughtful, and present—not just then, but throughout my entire life. She was interested in how the pictures made her feel.

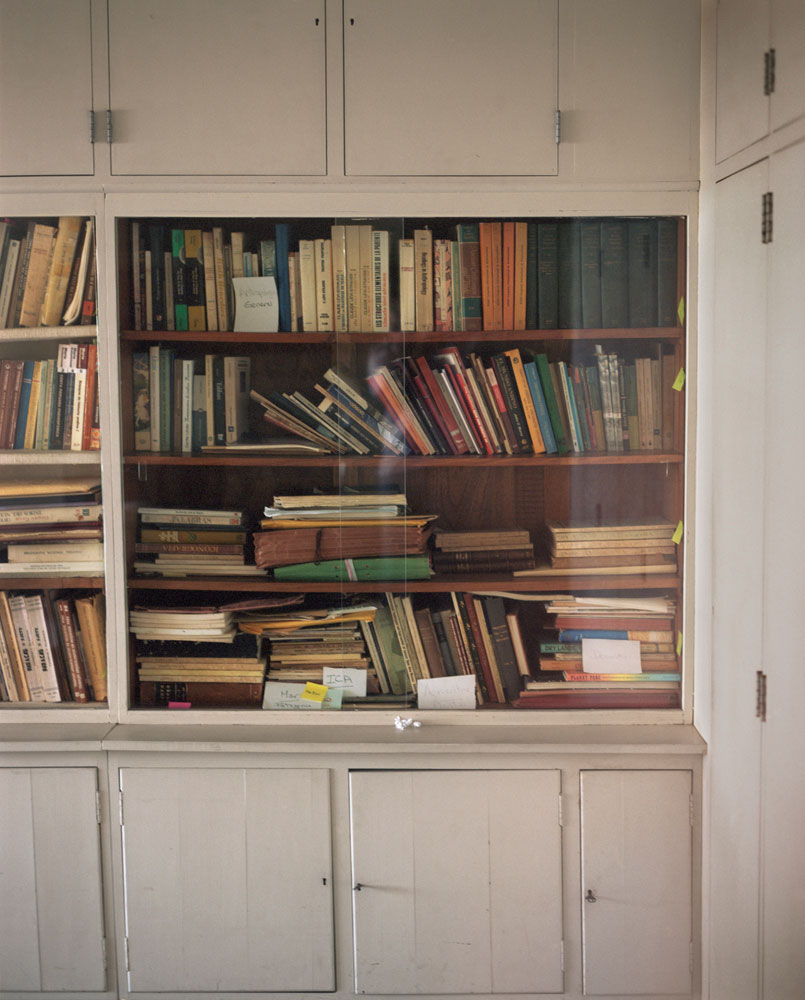

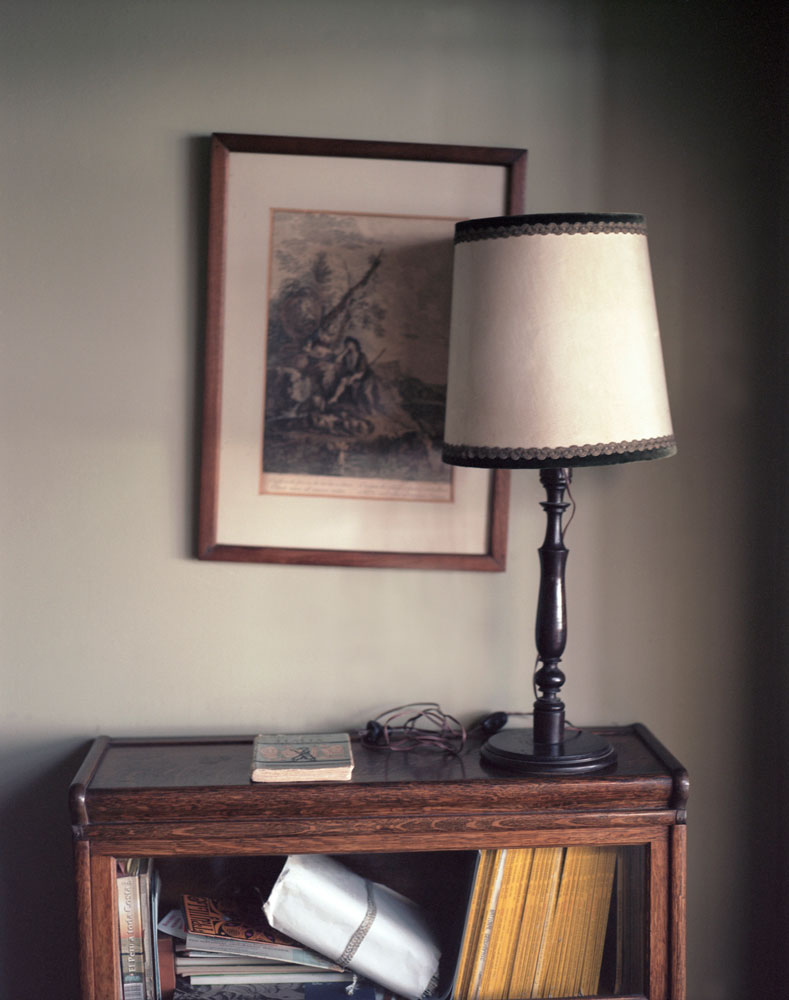

My Nonna was a woman of few words—in lieu of emotional goodbyes she would simply look me directly in the eyes and then kiss my cheek as she held my face in her palms. She slept on a simple twin–size bed, surrounded by her life’s work in a large room that doubled as her study, overlooking the ocean. I recall the clacking of her typewriter and later her computer’s keyboard. Her writing was always formal and poetic. She made her words dance in a way that only the Spanish language can afford—even in casual emails to her teenage grandson. She wrote to me in elegant and sophisticated ways. I felt seen.