ESSAY

The African American Snapshot Matters

All images from the collection of Robert E. Jackson unless otherwise noted

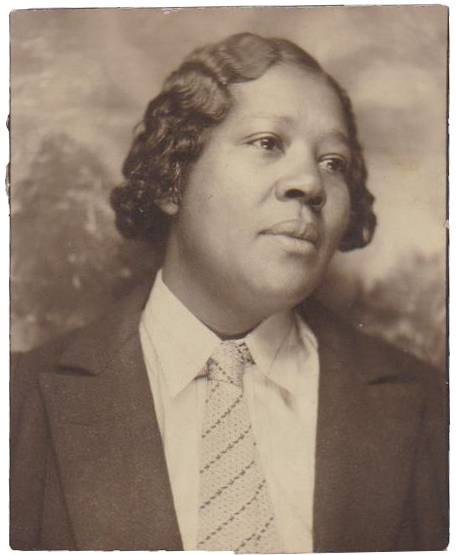

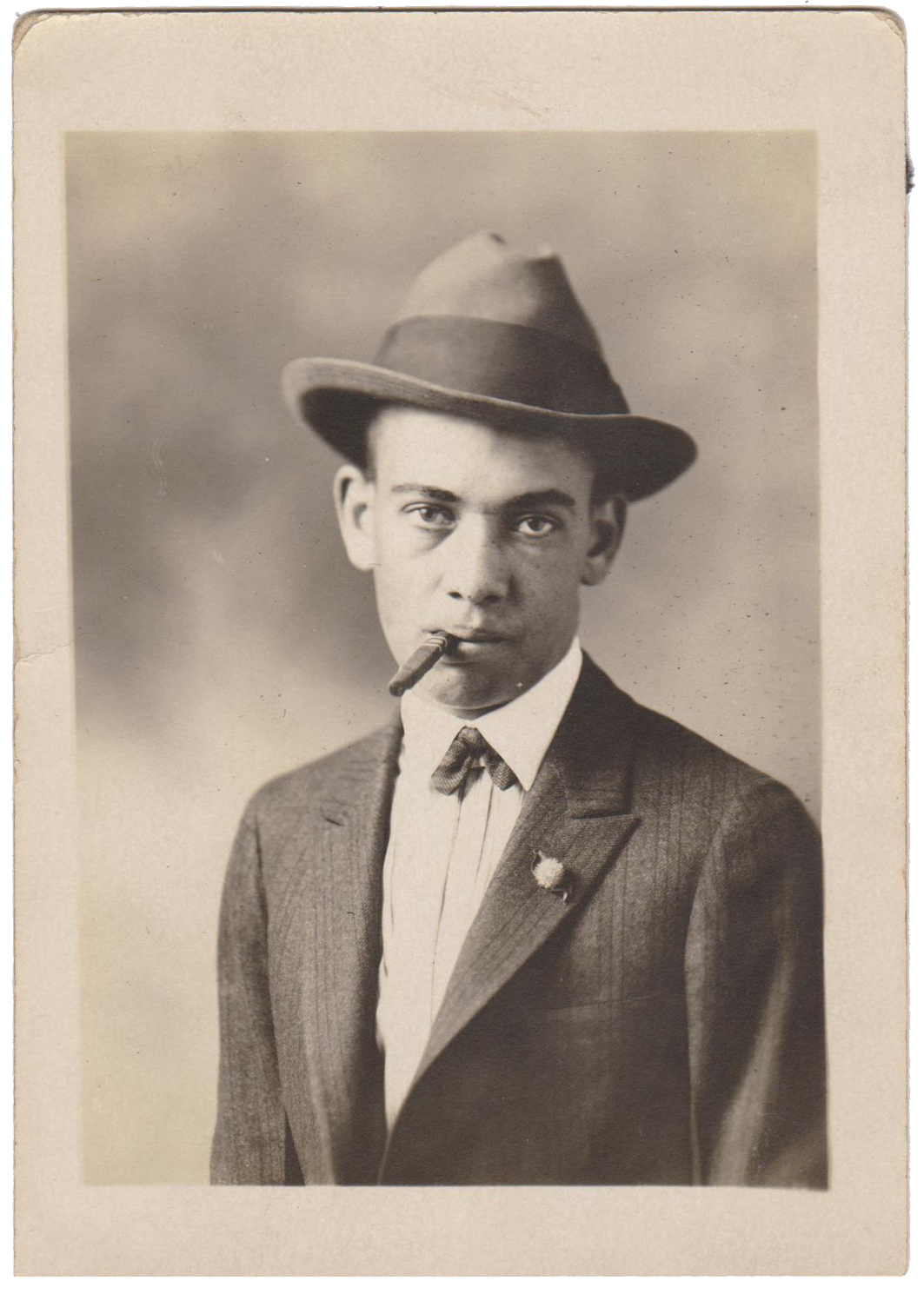

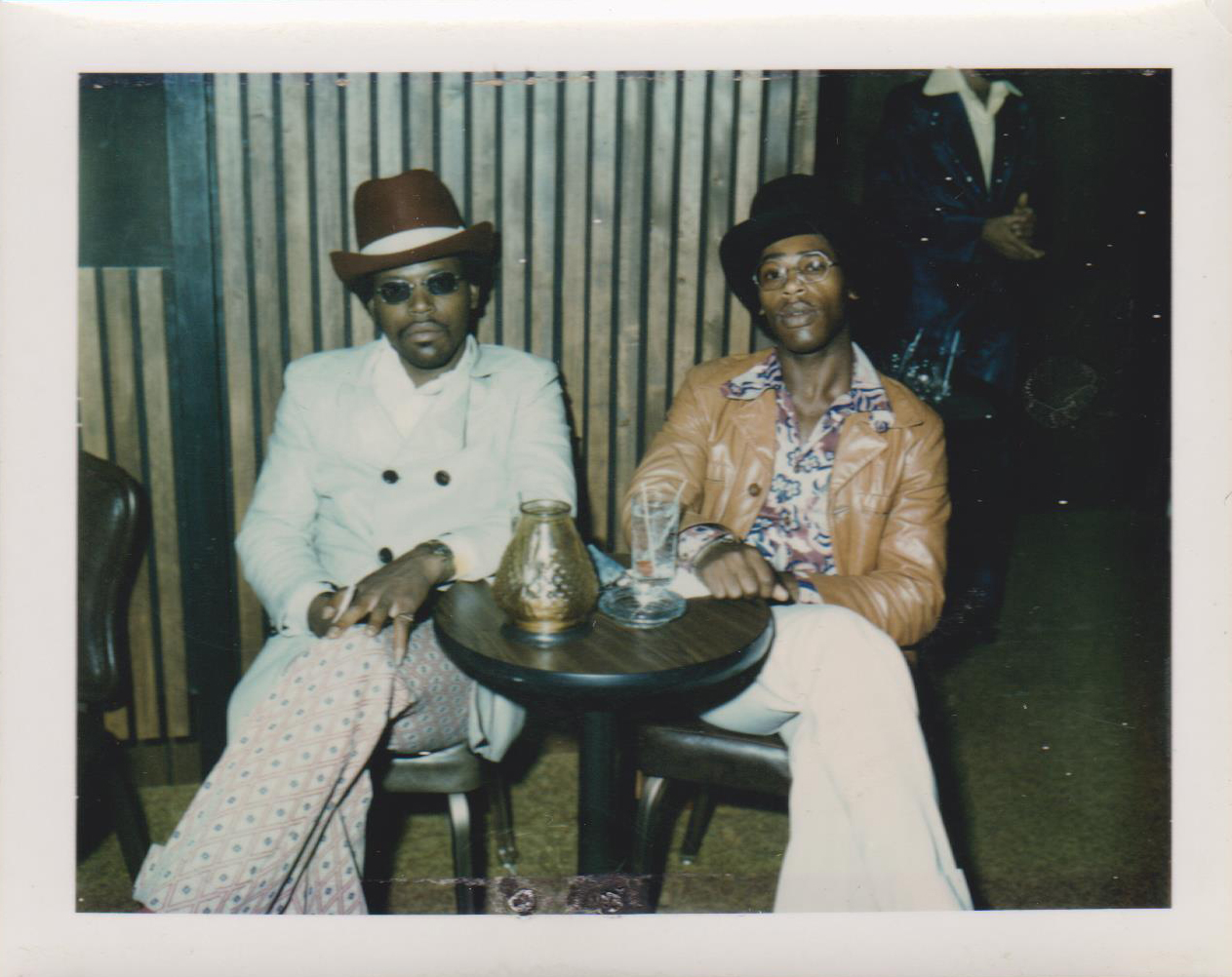

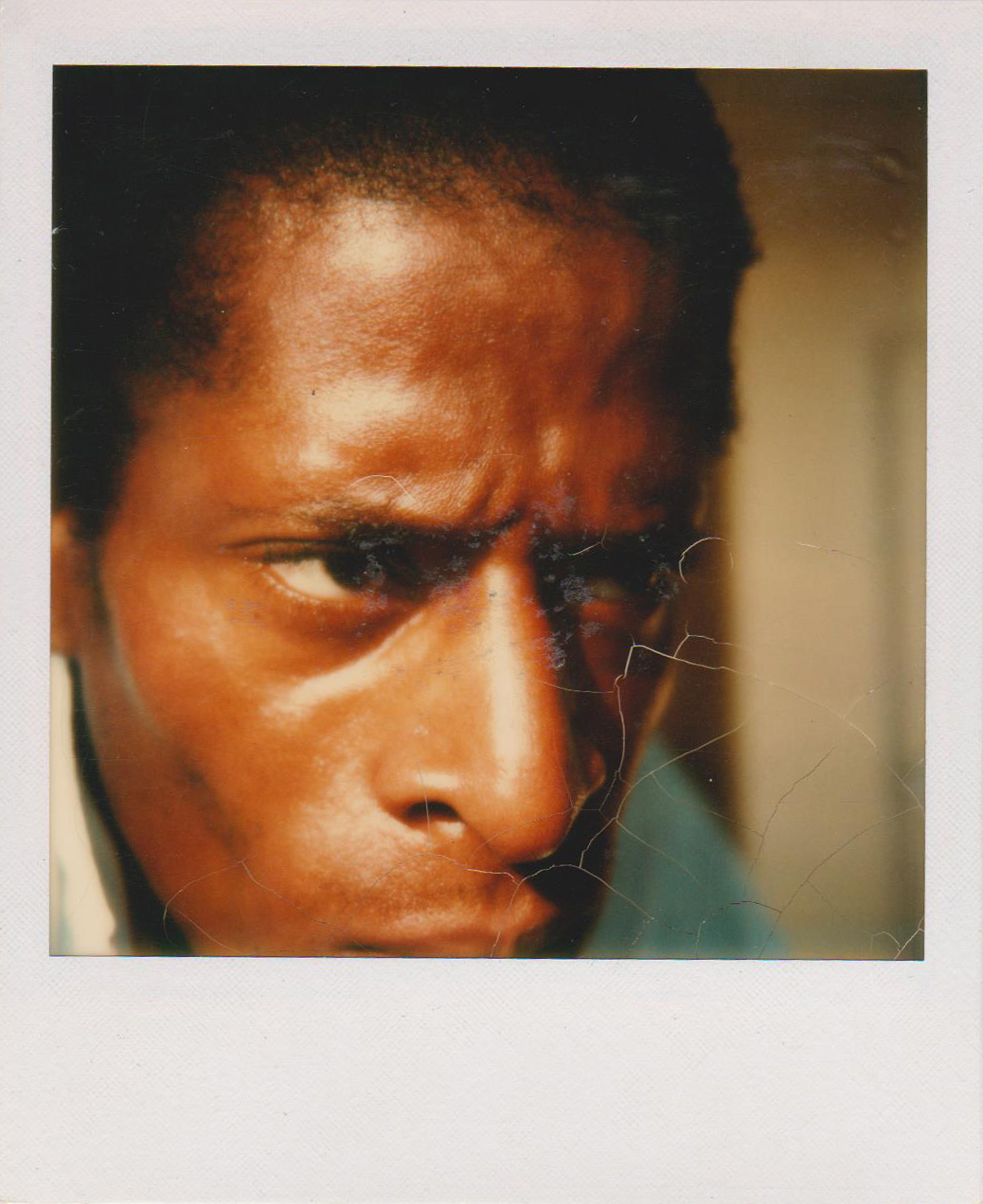

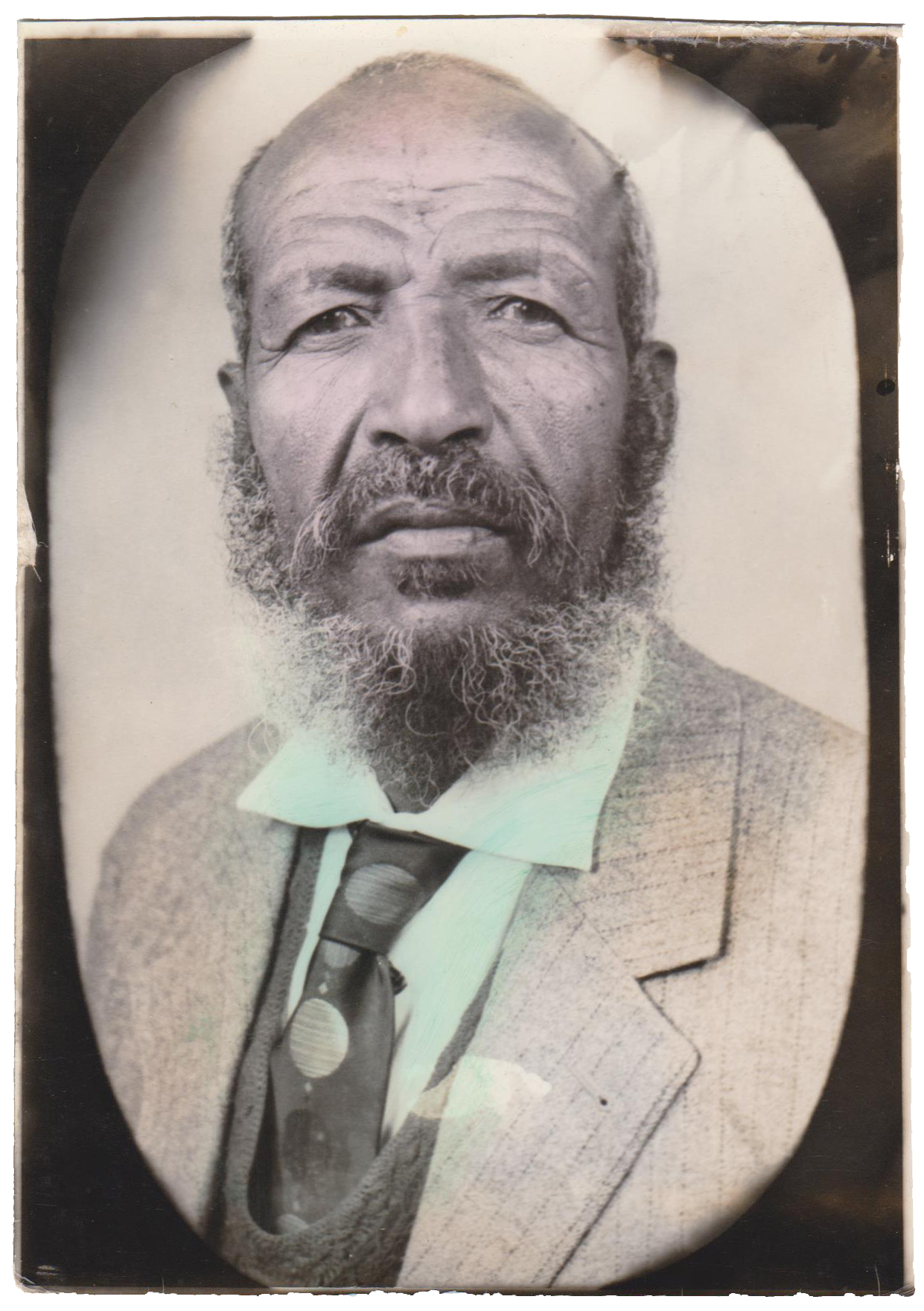

Representation of Black people in popular and vernacular culture throughout the last two centuries has been chiefly at the hand of White people. Without an outlet to represent one's self, the Black image took on generations of unfair interpretation, making snapshots of Black private life treasured tokens of American vernacular history today. Included here are snapshots from the collection of Robert E. Jackson, a wide range of images spanning from intimate and casual, to formal and solemn, from photo booths to color polaroids.

During the era of slavery, fear of rebellion manifested in the imagined notion of Black people as savages. Throughout the Reconstruction Era (1863-1877), Whites continued to oppress the Black person via caricatures and illustrated depictions of them as brutes. Though photography was invented in 1839, and by the 1870s it was a rather mobile process, depictions of Blacks in photographs were rare and largely controlled by Whites. It’s not until the twentieth century that snapshots and studio portraiture become more accessible and the Black person enters the vernacular tapestry of America through self-representation. However, this growing access to casual photography also resulted in an increased circulation of degrading images, such as harrowing depictions of lynchings, for example, which circulated as photo postcards. The early twentieth century also saw an increase of caricatured representation in movies and the media. D.W. Griffith's film Birth of a Nation (1915), told the story of a White Southern family from the days of slavery through the Civil War and into Reconstruction, the film showed images of Black brutes abusing their newfound freedom by perpetuating violence against Whites. Worse was their portrayal of the Brute as a sexual predator played by a White actor in blackface, while the Ku Klux Klan were portrayed as heroes

![Birth of a Nation (1915). Free Black shoots a White man.]() Birth of a Nation (1915). Free Black shoots a White man (source)

Birth of a Nation (1915). Free Black shoots a White man (source)

Caricatures of Blacks as brutes continued throughout the first half of the twentieth century in the image of uncivilized barbarians in comic strips, TV, and commercialized products, and continued through the latter part of the century with Blacks being portrayed as thugs in Hollywood movies. Most prevalent in the twenty-first century has been the image of young Black men in the media, often presented as thugs and delinquents, as a aggressors instead of victims when they are murdered by White police. It has been astonishing the ease with which these cases are dismissed under the pretense that the White person “feared for their life,” even when there is ample evidence that the Black person was compliant and unarmed. This “fear” is the same fear that created the Black caricature of the 1860s, and is the same fear that leads a picture editor to choose an image of Michael Brown—who was killed by police in Ferguson, MO—pictured from below, as a towering figure with a stern look, sagging clothes, and a peace sign that White culture interpreted as a gang sign, versus the more empowering image of him in a graduation cap and gown—the brute is an easier sell. During the Trayvon Martin trial, the hoodie became a cultural symbol. This has lead to heightened attention to how the media chooses to present Black males; in 2014 a Twitter campaign drew over 200,000 users to repost the hashtag #iftheygunnedmedown, which poses the question “If they gunned me down, what photo would you use?” The choice to always depict the Black male as an aggressor is, in fact, a choice; just as the choice the highlight a white rapist's athletic accomplishments over his crime is also a choice.

![James Van Der Zee, Wedding Party, 1923. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York]() James Van Der Zee, Wedding Party, 1923. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

James Van Der Zee, Wedding Party, 1923. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

Birth of a Nation (1915). Free Black shoots a White man (source)

Birth of a Nation (1915). Free Black shoots a White man (source) James Van Der Zee, Wedding Party, 1923. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.

James Van Der Zee, Wedding Party, 1923. Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York.